COVID-19 and Reopening Schools: Nine Questions and Answers from Science to Useful Tools

School reopening guidelines are beginning to roll out from state agencies and school districts are developing plans for the 2020-21 school year. Texas released their guidelines yesterday, which includes a requirement that schools must offer on-campus instruction for any parents that want it and also offer remote learning for parents that are not yet comfortable returning to school. In Texas, masks will be required for students over the age of 10 and health screening for all students and staff. Next week the governor of my state, NH, is expected to release guidelines for reopening schools in the fall. It's anticipated the NH guidance will cover everything from physical distancing guidelines in classrooms to extracurricular activities and bus transportation. Districts in NH are expected to have some flexibility (the state’s motto is “Live Free or Die”). Just this week President Trump and Education Secretary DeVos weighed in advocating for a complete reopening of schools downplaying the virus and asserting that political rivals would like schools to stay closed. Lily Eskelsen García, the president of the National Education Association (NEA), the nation’s largest teachers’ union shot back, “No one should listen to Donald Trump or Betsy DeVos when it comes to what is best for students.” The NH chapter of the NEA put out a press release last week that asserted that the state (and schools) should be investing in remote learning and plan to implement this model of education until January when a “vaccine could be available.” School leaders and school boards are trying to make the best decisions for how to open school in the fall, so this new injection of political rhetoric is likely to muddy the waters. In this blog entry, I plan to discuss what has been learned thus far about the virus and schools and how this information might be used to make less emotionally charged decisions about opening school in the fall.

I will answer some common questions about the virus.

How likely are kids to get sick? How sick do they get? How likely are they to transmit to someone else once they are sick?

The topline message on these questions is basically good news based on available evidence: The best available evidence shows that children may be somewhat less likely than adults to get COVID-19, are definitely much less likely to become severely ill if they do get it, and appear to be less likely to spread the virus that causes COVID-19. Before we dig a little deeper into these findings, it is worth stating that despite this finding, we must reinforce behaviors that reduce risk including social distancing (when possible), washing hands, and wearing face masks.

Several studies have shown that children are less susceptible to catching COVID-19 than adults (and no known studies that show children are more likely). Some examples of studies:

A CDC Morbidity and Mortality report from January through May found that the overall incidence of COVID-19 cases was 51 per 100,000 population among children 0-9 years old and 118 per 100,000 among those 10-19, compared to 492 per 100,000 among those 30-39 years old and 902 per 100,000 among those over 80 years old.

Iceland tested 15% of its total population for active infection and found children were half as likely to be infected as adults in both targeted and general population testing. In Iceland’s general population screening, no children under the age of 10 tested positive, despite nearly 1% of the overall sample testing positive.

In terms of transmission, limited evidence suggests that children may play a smaller role in the transmission of COVID-19 than adults. One of the primary reasons for closing schools is to reduce the spread of disease. This tool has been used effectively to stem the tide of influenza outbreaks in the past, but if children do not easily transmit COVID-19, then this may not be an effective strategy. Some of the studies that support the claim that children do not transmit as readily as adults:

A tracing and testing investigation of 735 classmates and 128 school staff did not identify any infected staff members among the 30% tested and identified only two students who may have been infected as a result of school exposure.

The YMCA and New York City Department of Education, which have served tens of thousands of children and thousands of staff, have not yet reported any clusters or outbreaks despite being open through the pandemic to serve the essential workers (e.g. doctors, nurses, bus drivers). (NOTE: It will be worth watching the data coming out of Texas where there are over 1,500 COVID cases linked to staff and children in daycares. About 1/3 are children and whether these are linked to the daycares - over 1,200 are open - is unclear as the data are slow to be available).

Did school closures work to stop COVID-19 spread?

Early evidence suggests that the impact of school closures was probably smaller than many of the other public health measures deployed at the same time. In many countries, schools have reopened (usually with limitations) without having caused increases in new cases. Schools have rarely been the sites of outbreaks or contributed substantially to COVID-19 transmission. This doesn’t mean that schools are encouraged to proceed with reopening as if nothing has changed, but that it is possible to reopen without causing hot spots to emerge.

In an increasing number of countries where cases were already trending downward before schools reopened, there is no evidence of a resurgence associated with the reopening.

Planning guidance from the CDC on reopening schools is really useful: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/community/schools-childcare/guidance-for-schools.html

What impact do school closures have on academics and social-emotional factors?

In short, school closures have been shown to have significant negative impacts on education.

First, some models project that elementary and middle school students could return to school in fall 2020 with a 30% reduction in learning gains in reading (compared to typical growth). Learning gains in math are projected to be worse.

Second, school closures are likely to increase performance gaps between high- and low-achieving students.

Third, students tend not to be as engaged in remote learning. Teachers in two separate surveys estimated that only about 60% of their students were regularly participating or engaging in distance learning. In Boston, one in five students were virtual dropouts .

Fourth, the impact on mental health may be even greater. Overall, investigators found that social isolation and loneliness increased the risk of depression, as well as the possibility of anxiety at the time of loneliness, which was measured between 0.25-9 years later. In fact, a study of Chinese students restricted to home during the COVID outbreak in Wuhan showed that these students had a significant risk of depressive symptoms.

What do scientists say about reopening schools?

The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) also released guidance last week regarding returning to school and they argued that every effort should be made to return to in-person schooling. The AAP guidance covers everything from PPE to sanitizing regimes, but it also notes “schools should weigh the benefits of strict adherence to 6-foot spacing rule between students with the potential downside if remote learning is the only alternative.

Outside the U.S., German pediatric, infectious disease, and public health societies have published recommendations for the reopening of German schools without “excessive” restrictions. This group argued that since the prevailing evidence shows that children are less susceptible, less impacted, and less likely to transmit to adults or other children schools and daycares should “promptly be reopened” (taking into consideration regional infection rates). They go on to state, “For children, this should be possible without excessive restrictions, such as clustering into very small groups, implementation of barrier precautions, maintaining appropriate distance from others or wearing masks.” The German scientists recommend for those at a significantly elevated risk of complications due to COVID there should be an individualized plan, rather than creating a solution that accounts for rare cases.

Given that the mounting evidence is that schools are low-transmissions environments for children and adults, British scientists have called for schools to be reopened immediately, including for children with pre-existing underlying conditions.

What tools exist to evaluate regional spread?

Being informed about COVID is vital during the process of reopening schools since much of the work boards and leaders will do will include talking to parents, students, and teachers. Four tools that are helpful for understanding the trends in the virus in your state (and county) are the New York Times COVID coverage, rt.live, COVID ACT Now, and Pandemics Explained.

The New York Times COVID data page has extensive data by state and county showing trends in cases and deaths. It also shows the locations of clusters and hot spots. These data are important to look at prior to engaging in any discussion about opening schools. If a county is showing a drastic increase in cases (e.g. Leon County, FL) the conversation about the type of opening is different from a county that has the virus in-check (e.g. Grafton County, NH).

rt.live measures how fast the virus is growing. When thinking about opening schools in the fall, this measure might be helpful. In states where the Rt value is below 1.0, the virus is spreading slowly in the community and it is much safer to allow groups to gather. Where the Rt value is above 1.0, the spread is too fast to be controlled without behavioral changes. Rt value alone should not be used to decide whether to reopen schools (note discussion about how unlikely schools are to become super spreader locations) but is another piece of data. In NH, the Rt value is 0.91, which means community spread is relatively low. On the other hand, Rt value is 1.21 which indicates community spread is quick and means that convincing the public that schools are safe to open will be more difficult (see above discussion about how children are less likely to contract and transmit COVID).

The COVID Act Now data are useful for seeing a small set of measures of how well states and counties are performing in controlling the virus and preparing for outbreaks. The situation in Vermont (rated “On Track to contain COVID”) is different from Arizona (rated “Active or imminent outbreak”) and this should be considered in reopening schools.

Pandemics Explained is a COVID Risk Level dashboard that will show you whether you live in a COVID hotspot.

What tools are available to assess risk mathematically?

19 and Me: COVID-19 Risk Score Calculator is a helpful tool for calculating susceptibility and impact risk. The calculator allows the user to enter basic data about themselves and returns risk for contracting COVID and risk for certain outcomes if they do contract the virus. The calculator does not take into consideration the reality that children are less likely to transmit COVID and that schools are not likely to be super spreader environments, but it is still a useful starting point for a conversation. For example, a 55-year-old in my zip code that has 50+ people that they have direct contact within a week (close contact over 10 minutes), lots of indirect contacts through their family members (n=100), and follows basic guidelines on masks and hand hashing has a .0012% chance of contracting COVID. That is considered a relatively low-risk scenario. Reducing the direct and indirect contacts by half (25 direct and 50 indirect per week) reduces the risk of contracting to .00061%. The Risk Score Calculator gives us insight into how our behaviors can impact our risk of contracting COVID. The risk is going to look different in Tallahassee, Florida where the virus is spreading.

What about what parents and staff think?

Panorama has surveys that you can use to capture what parents and staff think about returning to school in the fall. You can download the surveys at the Panorama website and (I think) you can use the surveys for free. You can also pay for their suite of analytics. Surveying parents and staff is useful for understanding where these important stakeholders stand. Regardless of the results, the job of leaders and the board is to talk to these stakeholders about the course of action you intend to take. Surveys are only a first step. The most important step is listening and doing everything you can to mitigate the concerns that stakeholders have about the plan for reopening.

Try to anticipate questions that major stakeholders are going to ask. For example, teachers will need to be convinced that it is safe for them to return to work and they have a lot of questions. NJ teachers have been crowdsourcing questions (over 375) about school reopening that are useful for boards and leaders to think about.

Consider creating a local FAQ that discusses the current science, plans to mitigate risk, and plans in the event of an outbreak (German researchers opposed closing schools in the event of a single positive test).

Is there a checklist for school opening?

Sort of.

A useful place to start is with the CDC checklist for reopening schools. Not all of these recommendations are practical (e.g. installing sneeze guards between desks), but this is the best place to begin in the process.

What else?

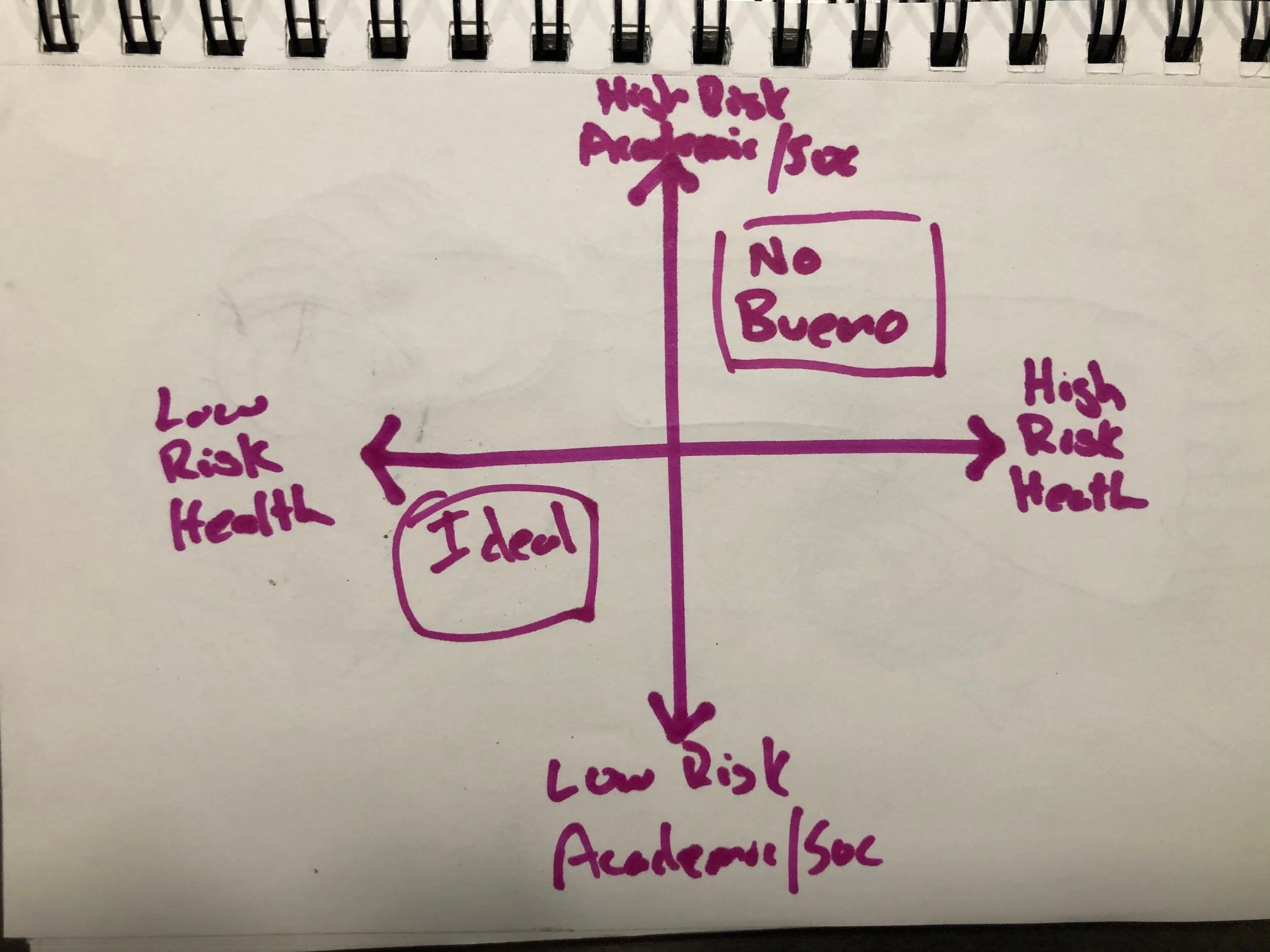

Consider creating a Risk Matrix when discussing reopening plans. Put risk to health on one axis and risk to academic and social well being of students on the other. You can then take each of the scenarios your district is considering and place them on the matrix. In the county where I live in NH, the risk for contracting COVID is exceeding low, which means almost any option for returning to school has a “Low Health Risk”. Remote learning only has a lower health risk than full in-person school (assuming the adults behave as if a “stay at home” order were in place), but the risk is only minimally higher (both are a low risk). On the other hand, remote learning is an abysmal option for addressing student academic and social-emotional needs relative to in-person learning. Remote learning will always be “High Risk to Academic/Social Development” and in-person school will always be “Low Risk to Academic/Social Development”. Other options (e.g. hybrid scenarios) will fall in-between (although, there are no data to support these approaches to learning).

Think hard about what to do in the event that cases begin to climb in the community or a student or staff member tests positive. The German scientists argue that one case should not close schools down. Instead, think in terms of multiple variables (how many cases in the building and how wide-spread in the community). The Fulton County Schools (Georgia) have an Interim School Closure Decision Matrix to be used in the event that cases rise in the community or members of the school community test positive.